Patrick Pearse, also known as Pádraig in Irish, was a prominent Irish nationalist, educator, poet, and one of the leaders of the Easter Rising of 1916. A modern father of our nation, here is a brief biography of Patrick Pearse:

Early Life: Patrick Henry Pearse was born on November 10, 1879, in Dublin, Ireland. He was the son of James Pearse, a sculptor, and Margaret Brady Pearse, a devout Irish-speaking Catholic. Pearse was raised in a home where Irish language, culture, and nationalism were highly valued.

Education: Pearse attended the Christian Brothers School and later the Royal University (now University College Dublin), where he studied law and languages. He was deeply influenced by Irish history, literature, and the Gaelic revival movement, which sought to promote Irish language and culture.

Educator and Activist: Pearse became a schoolteacher and dedicated himself to promoting Irish language and culture through education. He founded St. Enda's School (Scoil Éanna) in Dublin in 1908, which aimed to provide a nationalist education rooted in Irish language, history, and traditions. Pearse's educational philosophy emphasized the development of the whole person and the cultivation of a strong sense of Irish identity and patriotism.

Political Involvement: Pearse was actively involved in various nationalist and cultural organizations, including the Gaelic League, which promoted the Irish language, and the Irish Volunteers, an organization formed to resist British rule in Ireland. He was a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), a secret revolutionary organization dedicated to achieving Irish independence.

Easter Rising: Pearse emerged as one of the key leaders of the Easter Rising of 1916, a rebellion against British rule in Ireland. He served as the commander-in-chief of the Irish Volunteers during the Rising and acted as the president of the Provisional Government, which declared Ireland's independence. Pearse famously read the Proclamation of the Irish Republic outside the General Post Office (GPO) in Dublin on Easter Monday, April 24, 1916.

Execution and Legacy: The Easter Rising was ultimately suppressed by British forces, and Pearse, along with other leaders, was captured and sentenced to death. He was executed by firing squad on May 3, 1916, at the age of just 36. Pearse's execution, along with those of other rebel leaders, galvanized public opinion in Ireland and led to increased support for the cause of Irish independence. He is remembered as a hero of the Irish nationalist movement and a symbol of the fight for Irish freedom.

Patrick Pearse's life and legacy continue to be celebrated in Ireland, where he is revered as one of the founding fathers of the Irish Republic and a visionary leader who sacrificed his life for the cause of Irish independence. His contributions to education, literature, and the struggle for Irish language and culture remain influential to this day.

Patrick Pearse's key ideas were deeply rooted in Irish nationalism, cultural revivalism, and the pursuit of Irish independence. Here are some of his key ideas:

Irish Cultural Revival: Pearse believed in the importance of preserving and promoting Irish language, literature, and traditions as essential components of Irish national identity. He was a leading figure in the Gaelic revival movement, which sought to revive and celebrate Irish language and culture as a means of asserting Irish identity in the face of British colonialism.

Educational Philosophy: Pearse's educational philosophy emphasized the importance of providing a nationalist education that nurtured a strong sense of Irish identity and patriotism. He founded St. Enda's School (Scoil Éanna) in Dublin with the aim of instilling in students a deep love for Ireland and its culture. Pearse believed that education should cultivate the whole person and prepare individuals to contribute to the national struggle for independence.

Irish Nationalism: Pearse was a passionate advocate for Irish independence and self-determination. He believed that Ireland should be free from British (or other) rule and that the Irish people should have the right to govern themselves. Pearse saw the struggle for independence as a moral imperative and a fundamental aspect of the Irish national identity.

Sacrifice and Martyrdom: Pearse glorified the idea of sacrifice and martyrdom in the pursuit of Irish freedom. He believed that the cause of Irish independence was worth sacrificing one's life for and that martyrdom would inspire future generations to continue the struggle. Pearse's own willingness to sacrifice his life for the cause during the Easter Rising exemplified his commitment to this idea.

Social Justice: While Pearse is primarily remembered for his nationalist and cultural activities, he also expressed concern for social justice issues, particularly the plight of the poor and marginalized in Irish society. He believed that an independent Ireland should strive for a more just society that prioritized the welfare of all its citizens.

Overall, Patrick Pearse's key ideas revolved around Irish nationalism, cultural revivalism, educational reform, and the pursuit of Irish independence. His vision of Ireland as a sovereign nation, rooted in its language, culture, and history, continues to resonate with many Irish people and remains influential in Irish politics and culture.

Pearse’s Spiritual Nationalism

Patrick Pearse's spiritual nationalism challenges reductionist materialist philosophies by emphasizing the holistic nature of human experience and identity. This perspective resonates with Iain McGilchrist's critique of modern materialism, which often prioritizes analytical, left hemisphere thinking over holistic, integrative approaches that engage both hemispheres of the brain.

McGilchrist's work, particularly in "The Master and His Emissary," highlights the dominance of the left hemisphere in contemporary Western culture, which tends to reduce reality to simplistic, one-dimensional terms. This reliance on left hemisphere thinking contributes to the narrowness of modern materialism, which overlooks the rich complexity of human experience and cultural identity. As part of this materialist vogue, nationalism has often been reduced to its black and white dimension.

Pearse's spiritual nationalism, with its emphasis on the spiritual and cultural dimensions of Irish identity, challenges the reductionism of materialist philosophies by highlighting the interconnectedness of culture, spirituality, and human consciousness. By engaging both hemispheres of the brain, Pearse's nationalism offers a more holistic understanding of Irish identity that transcends simplistic, one-dimensional interpretations.

In this light, Pearse's vision of Irish nationalism serves as a reminder of the importance of embracing a balanced, nuanced approach to understanding reality—one that acknowledges the contributions of both hemispheres of the brain and recognizes the profound spiritual and cultural dimensions of human existence.

By challenging reductionist materialism, statism, and perverse ethno-nationalism, Pearse's nationalism opens space for a more expansive and integrated understanding of identity, one that honours the complexity and richness of human experience.

Patrick Pearse's tripartite view of the nation, which he espoused, was deeply rooted in his understanding of Irish nationalism and cultural identity. It generally encompassed three key aspects:

The Gaelic Past: Pearse emphasized the importance of Ireland's Gaelic past as the foundation of its national identity. He believed that Ireland's ancient language, culture, and traditions were central to its essence as a nation. Pearse celebrated Ireland's pre-colonial history and sought to revive and preserve Gaelic language and culture as a means of reconnecting with the nation's spiritual and cultural heritage.

The Christian Faith: Pearse also viewed the Christian faith – particularly Catholicism - as an integral part of Ireland's national identity. He saw the Church as a unifying force that provided moral and spiritual guidance to the Irish people. Pearse's nationalism was often intertwined with Catholicism, and he believed that Ireland's major Christian faith played a crucial role in shaping its cultural and social fabric.

The Irish Landscape: Pearse's conception of the nation also encompassed the physical landscape of Ireland. He celebrated the natural beauty of the Irish countryside and saw it as a source of inspiration and spiritual nourishment for the Irish people. Pearse believed that Ireland's landscape reflected its unique character and contributed to its sense of national identity.

This tripartite view of the nation, with its emphasis on Gaelic culture, Catholic faith, and the Irish landscape, provided Pearse with a holistic framework for understanding Irish nationalism and cultural identity. It highlighted the interconnectedness of language, religion, and land in shaping the Irish national consciousness.

In terms of scaling societally, Pearse's tripartite view of the nation can be seen as analogous to Plato's tripartite view of the soul in "The Republic." Plato posited that the individual soul consists of three parts: reason (logistikon), spirit (thumos), and appetite (epithumia).

Similarly, Pearse's tripartite view of the nation could be understood as consisting of cultural & intellectual heritage (Gaelic past), spiritual values (The Christian faith), and physical environment (Irish landscape).

Just as Plato argued that a harmonious balance among the three parts of the soul leads to individual virtue and justice, Pearse believed that a harmonious integration of Gaelic culture, Christian faith, and the Irish landscape contributes to the well-being and integrity of the Irish nation. This holistic view suggests that the health and vitality of a society depend on the cultivation and harmonization of its cultural, spiritual, and environmental dimensions.

The tripartite perspective is echoed in Wendell Berry’s classic, The Unsettling of America, and can help us to appreciate their interrelated nature:

“The word agriculture,” Berry writes in The Unsettling of America “after all, does not mean ‘agriscience,’ much less ‘agribusiness.’ It means ‘cultivation of the land.’ And cultivation is at the root of the sense both of culture and cult.

Bringing culture, spirituality, and land together, Wendell notes that ‘The ideas of tillage and worship are joined in culture. And these words all come from an Indo-European root meaning both ‘to revolve’ and ‘to dwell’.

He goes on to suggest that ‘To live, to survive on the Earth, to care for the soil, and to worship, are all bound at the root to the idea of a cycle.”

I am confident that Patrick Pearse would agree, and we crave a nobler way of life. Pearse and his ilk have blazed a trail.

Now, let us give Pearse the final word on Ireland, specifically:

“If you strike us down now, we shall rise again and renew the fight. You cannot conquer Ireland; you cannot extinguish the Irish passion for freedom.

If our deed has not been sufficient to win freedom, then our children will win it by a better deed.”

― Pádraig Pearse

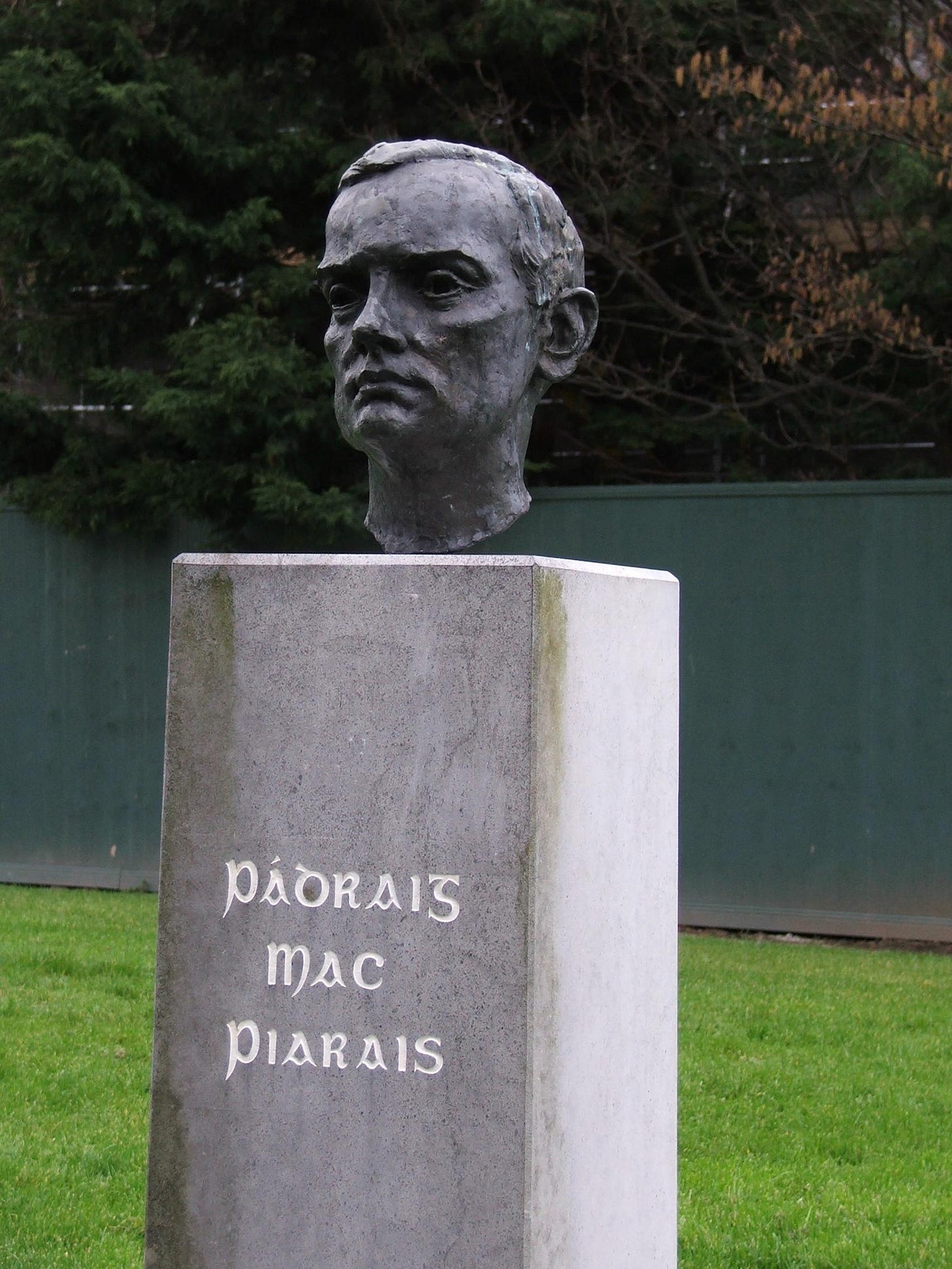

Pearse Statue, Padraig Pearse Park, Tralee, Co Kerry, Ireland

Crowds gathered at the graveside of O'Donovan Rossa. Pearse is centre-right (in uniform)